We are quite aware that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) kept the repo rate and the reverse repo rate unchanged at 4% and 3.35% respectively, being at a record low level. They have revised the inflation forecast from the current 5.6% to 4.2% by quarter 4 of FY 2022-23.

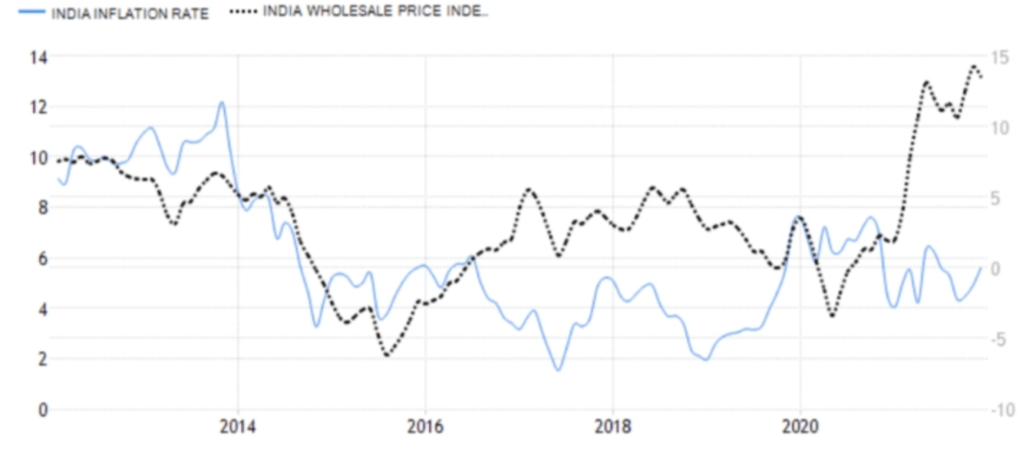

The most common metrics of measuring inflation are the Wholesale Price Index (WTI) and the Consumer Price Index (CPI). In layman’s terms, WPI measures the average change in price in the sale of goods or services in bulk quantity by the wholesale seller whereas CPI measures the change in the price in the sale of goods or services in retail i.e. direct to consumer/end-user. Price Index refers to a number that measures the degree by which the price of goods or services is increased with reference to a base year.

The above-mentioned forecast of 4.2% is for the CPI which appears to be quite lower than the WTI. This translates to a unique situation where the producers are facing the highest inflation in nearly two decades whereas the same is not being reflected by the CPI.

Under normal circumstances, the CPI follows the WPI (might be some lag) as increases in input prices are Ultimately passed on to the consumers. However, the current divergence has persisted over many quarters. This means that the manufacturers are unable to pass on the increase in input costs to the end-user which signals that the demands are quite low compared to the pre-covid situation. What it does is reduce the margins for the manufacturers which is quite evident from the quarter 3 performance results of FMCG, automobiles, chemicals etc.

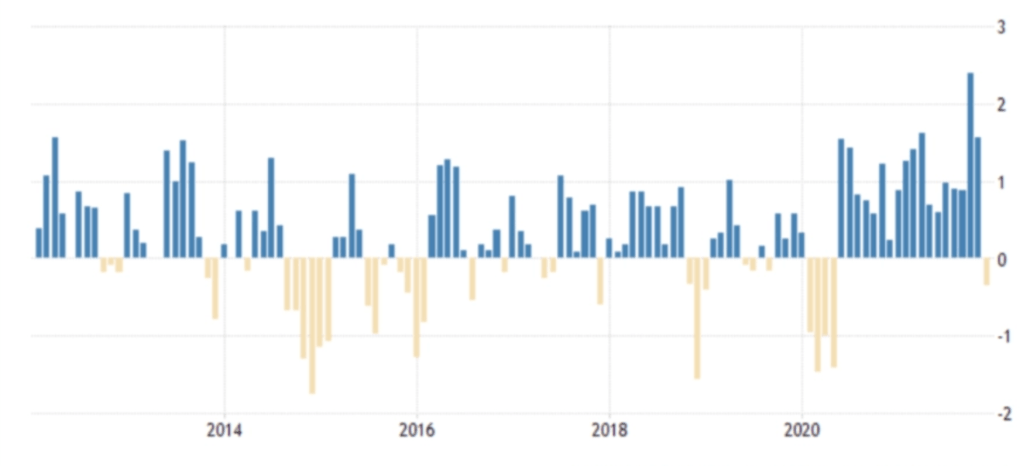

In December 2021, the WPI stood at a record two-decade highest at 13.6% year on year (YoY) slightly lower than 14.2% in November. The graph below shows that there has been a consistent rise of more than 1% to 1.5% month on month in the WPI since the second half of 2020.

However, the CPI is well within the limits of RBI’s target of 4% +/- 200 basis points. The CPI stood at 5.6% in December 2021, an increase from 4.9% in November. One can clearly see the divergence of the WTI from the CPi in the following graph.

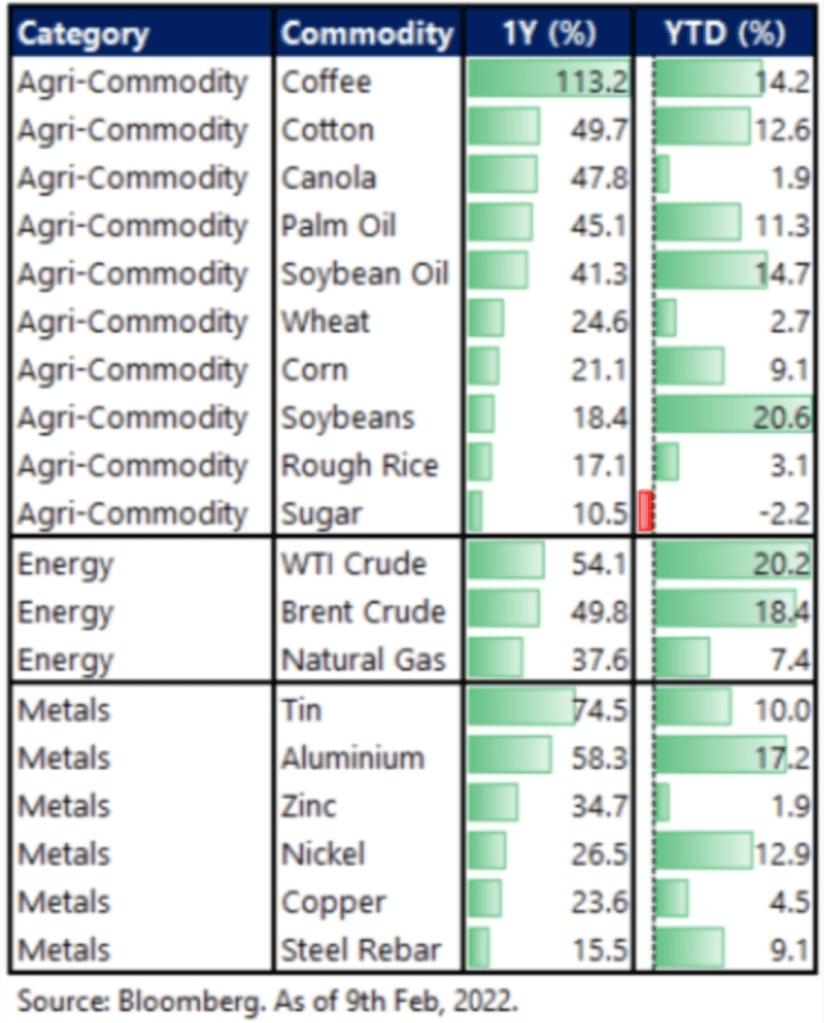

It has already been established that the manufacturers are facing margin cuts with the increase in input costs. The increase in the commodity costs, fuel costs, shipping costs with limited supplies, and war disrupting normal business had led to significant price hikes.

It is interesting to note that the sudden shift towards a “greener” future has led to something called Greenlfation. Investments in fossil fuels have been reducing whereas the greener sources of energy aren’t quite ready to serve the energy needs be it in terms of affordability, scalability, or supply constraints. All these have led to a lower supply of fossil fuels without equal offset on the demand side thereby leading to price hikes. This has further resulted in sizeable cuts in smelter production leading to a shortage of metals and pushing prices even higher.

As per the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), food prices remained at 10 years high with huge jumps in vegetable oil prices like palm oil, soybean oil, sunflower oil. Again impacting sectors like the chemical industries, FMCG, etc. that use these oils as an input

Overall we have entered a vicious cycle where the price of one commodity pushes the price of the other which then results in a domino effect. Breaking away from the cycle won’t be easy and would require some hard calls. Another question that needs to be addressed is should RBI change its stance of “inflation-targeting” introduced by Rajan? Is CPI the right yardstick that reflects the current situation? Well, uncertainties prevail and it will be interesting to see how the various agencies handle the situation.